What happened and why the sequence matters

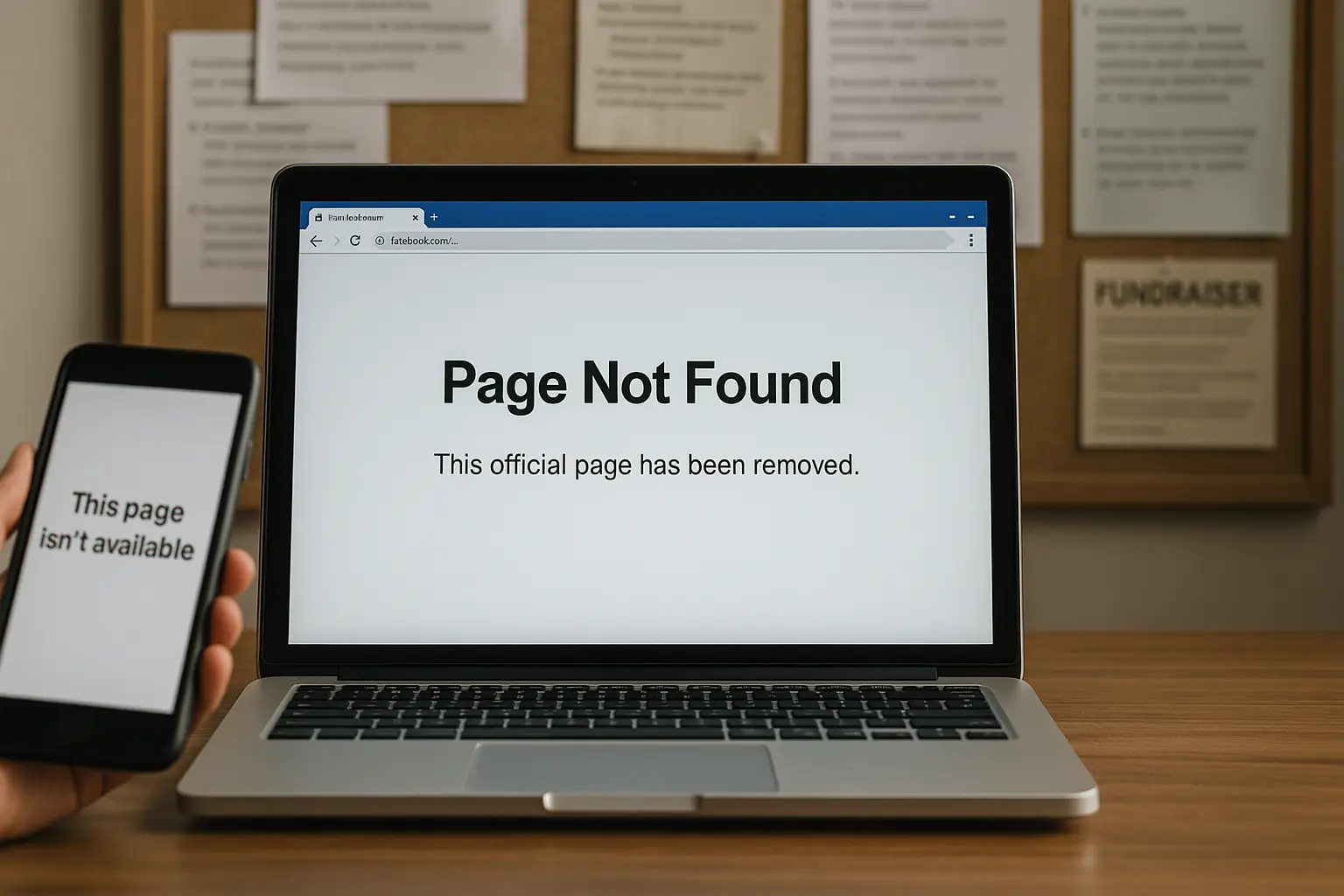

For months, Dehesa’s official Facebook page served as a practical bulletin board: field trip reminders, calendar nudges, photos from performances. In recent weeks, that page also became something else: a place where parents compared notes, pressed for clarity on decisions, and documented inconsistencies in real time. After several exchanges in which administrators made it known they disapproved of parents posting those questions on the page, the district took a step that is as sweeping as it is revealing: the page was removed entirely. No sunset notice, no link to an archive, no replacement channel for two‑way conversation.

The order of events is not contested: questions escalated; the venue vanished. You don’t need access to closed‑door conversations to see the pattern, it’s visible in what the public could see one day and could not the next. That timing, paired with the absence of any transparent transition plan, supports a straightforward inference about motive: leadership preferred control over conversation.

What exactly vanished

Deleting an official page doesn’t just tidy up a messy thread. It erases shared visibility, the capacity for parents to see each other’s questions and the district’s answers in one place, permanently accessible and searchable. It eliminates a contemporaneous record of how the district communicates with families. It also wipes out context that matters to future readers: what was promised, what was clarified, and what was contested at the time.

Equally important, the deletion collapses a community feedback loop. On a functioning page, soft pressure from peers incentivizes accuracy, from both the district and commenters, because misstatements can be corrected in the open. Take away the venue and you remove the friction that improves information.

Why this isn’t about “moderation is hard”

Moderating a school district page is work, but it is not an unsolved problem. A content‑neutral regimen exists: a published comment policy (time/place/manner, not viewpoint), keyword filtering for slurs and doxxing, rate limits to handle spam, post‑level comment controls for purely logistical announcements, periodic open‑thread Q&As, and a mirrored web portal governed by the same rules so that participation doesn’t depend on having a social account. Districts across California have implemented versions of these tools successfully.

Dehesa chose none of that. Instead of adopting neutral guardrails to keep the conversation civil, it removed the conversation.

Did they need a board vote to erase the page?

Dehesa didn’t take this to the dais. There was no agenda line, no public discussion, no vote, no minutes—just a vanished page and a quieter public. On paper, that omission will likely be defended as “administrative.” California school boards routinely delegate day-to-day communications decisions to the superintendent, and Education Code §§ 35161 and 35035 give cover for that structure: the board sets policy, the superintendent executes. Dehesa’s own social-media policy suite—Board Policy 1114 and its companion Administrative Resolution 1114 —reads the same way. It frames official pages as tools of the district, authorized and managed by the superintendent or a designee, with the familiar promises about accessibility, neutrality, and engagement. In that universe, throwing the switch can be painted as a staff call, not a governance act.

But delegation is not a blank check, and “we had the authority” is not the same as “we used it responsibly.” Dehesa’s policy language contemplates viewpoint-neutral moderation, published rules of the road, and continuity of communication—not the nuclear option when the conversation gets inconvenient. If leadership wants to argue this was merely an administrative tweak, then the administrative record should exist: a dated decision memo, the preservation logs, the export of posts, comments, and messages, and a transition plan that tells families where two-way conversation lives now. If those receipts aren’t there, what you have isn’t routine management—it’s a quiet shutdown of a public square.

There’s also a line the district cannot cross without tripping the Brown Act. A superintendent acting alone under delegated authority is one thing. A quorum of trustees nudging, coordinating, or directing the takedown by text or email is another. The law doesn’t require a vote to violate it; it requires a collective decision made outside public view. If board members, as a majority, effectively decided to disappear the page and left staff to press the button, that’s not administration—it’s an unnoticed meeting by another name.

Even setting the Brown Act aside, the records problem doesn’t go away. California treats social-media content about public business as public records. The Public Records Act governs disclosure, and local retention rules govern how long the district must keep its own copy. Deleting the forum didn’t delete those duties. If the page came down without verified exports and a retention pathway, the district didn’t “simplify communications.” It shredded context the public owns.

So did they “need” a vote? If the superintendent really acted within delegated bounds, a formal vote may not have been legally required. But the absence of a vote doesn’t sanitize the choice. A policy built to foster engagement was invoked to extinguish it; a delegation meant to keep government running smoothly was used to sidestep accountability; and a legal framework that presumes openness now has to contend with a decision that erased a living record. That’s the story here: not just what authority existed, but how it was exercised—and what that reveals about who this district believes the public square belongs to.

The legal landscape — and the hole Dehesa drove through

Two strands of law frame what happened: free‑speech constraints on public‑official social media and public‑records duties for local government.

Free speech & official pages. Courts have made clear that when public officials use social media to conduct public business: making announcements, soliciting feedback, or directing constituents to services, they can’t discriminate against speech because of viewpoint. That’s the heart of recent rulings clarifying when an official’s feed counts as state action and what limits follow.

Deleting an entire page is a different posture than selectively hiding comments or blocking particular parents. It may sidestep the most obvious “you removed me because you disliked my viewpoint” claim. But timing and context still matter. If a forum’s elimination is closely tethered to rising criticism, it functions as a form of suppression by other means: not silencing a parent, but depriving all parents of a public square. Courts analyze those facts carefully, and even if a district escapes a clean First Amendment claim, the move exacts a democratic price.

Public records & the duty to preserve. Here the risk is more concrete. Communications about district business on an official page — posts, comments, replies, and direct messages — don’t evaporate into “private” status because they happened on Facebook. In California, social‑media content concerning public business is treated as public records. While the Public Records Act compels disclosure of records that exist rather than dictating retention schedules, local‑records laws and widely adopted policies require agencies to keep their own copies or ensure an approved archiving method. Wholesale deletion without ensuring preservation is not streamlining; it is destruction of the public’s memory.

In plain English: if an agency deletes an official page without first exporting or archiving its content, it hasn’t cleaned house — it has thrown out the file cabinet.

The accountability ledger (what a well‑run district would be able to show)

A competent, transparent agency could put four receipts on the table the same day it removed a page:

Notice & transition. A dated announcement telling families when the page would come down, where the new two‑way forum would live, and how to subscribe.

Policy & neutrality. A published moderation policy emphasizing viewpoint neutrality (rules applied to behavior, not beliefs) and explaining time/place/manner limits tailored to school contexts.

Preservation plan. A verification that all posts, public comments, and messages related to district business were exported or captured by an approved archiving system and logged for retention.

Decision record. A short decision memo noting who authorized the change, what alternatives were considered, and what legal/records review occurred beforehand.

Dehesa produced none of those publicly. That silence is itself a finding.

How to reconstruct what leadership erased (parents’ playbook)

Document what you had. If you interacted with the page, capture your screenshots and download your message history. Label files with dates and context.

Track dead links. Keep the original URL of the page and any official newsletters or flyers that sent parents there. Dead links demonstrate that the page functioned as an official communications channel.

Mirror the forum. Stand up independent parent spaces and adopt a simple, civil code of conduct. Public oversight does not need the district’s permission.

Share receipts securely. If you possess exports, admin names, or written rules that were in effect, send them. We protect sources.

What this decision reveals about governance culture

Small districts often cite capacity: not enough hands, too many fires. But this deletion didn’t save staff time; it saved leadership from scrutiny. It substituted one‑way broadcasting for conversation, and it did so precisely when conversation mattered most. That is a strategic communications choice with governance consequences. Families learned that when dialogue became inconvenient, access was withdrawn.

What’s next will say even more. A district that values accountability will stand up a replacement with clear, neutral rules and will publish an archive of the old page. A district that values control will continue to push information outward while insulating itself from feedback.

How the case law lands here—and why it matters

Start with the Supreme Court’s reset. In Lindke v. Freed (2024), the Court said a public official’s social-media conduct triggers First Amendment limits when two things are true: the official has actual authority to speak for the government on the subject, and in the relevant posts the official purported to exercise that authority. That’s the new state-action test. Apply that to Dehesa: the district’s Facebook page carried official announcements to parents; it was branded as the district’s voice; and it was administered under the superintendent’s delegated authority. That constellation looks like “actual authority” plus “purported exercise” under Lindke—meaning constitutional constraints attach to how that space is run.

Lindke’s companion case, O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier (2024), came from San Diego County and involved school trustees blocking parents on Facebook and Twitter. The Supreme Court vacated the Ninth Circuit’s earlier ruling and told the lower court to re-decide under Lindke’s two-part test. On remand in Garnier v. O’Connor-Ratcliff (9th Cir. May 14, 2025), the court held the trustee acted under color of state law and that blocking the parents violated the First Amendment. Why? Because she used her page to conduct official business and then excluded critics based on their speech. The Ninth Circuit’s opinion is useful here not just for the outcome, but for its factor-by-factor analysis of official use. A school official using social media to communicate policies, events, and decisions is squarely in “government speech channel” territory.

Dehesa didn’t block select parents; it deleted the entire page. That difference matters legally, but it doesn’t end the inquiry. The classic Garnier-style violation is viewpoint discrimination against identifiable users. Wholesale deletion looks, at first glance, more like shutting a forum prospectively. Yet courts do not ignore timing and context. If the forum’s removal closely tracked a spike in criticism, the effect mirrors retaliation: not silencing one parent, but eliminating the public square where dissent was visible. Lindke and Garnier together frame a question a court would ask here: was Dehesa using this page with actual authority to speak for the district, and did it eliminate that venue at the very moment constituents were engaging in protected speech? If yes, the legal risk shifts from “you blocked me” to “you dismantled a designated public channel to avoid protected criticism.” The doctrine is newer at that edge, but the facts are not friendly to a government defendant.

The governance law running alongside the First Amendment is California’s Brown Act. A superintendent can act under delegated authority, but a collective concurrence by a board majority—reached by email or text outside a noticed meeting—turns an administrative click into a Brown Act problem. The Attorney General’s guide and municipal handbooks are clear: serial communications that amount to a quorum decision are unlawful. If trustees coordinated a takedown off-calendar, that’s a separate violation even if staff executed the deletion.

Then there’s the records law overlay. California courts have long held that where a record lives does not decide whether it’s public: communications about public business are subject to disclosure even on personal devices or accounts (City of San Jose v. Superior Court, 2017). Social-media content used to conduct public business is therefore public record material; agencies can’t make it disappear by housing it on a platform they don’t own. That’s coupled with local-records retention duties (e.g., Gov. Code § 34090), and widely cited municipal guidance stresses that retention obligations are distinct from disclosure—meaning an agency must preserve its social-media records even before anyone requests them. If Dehesa deleted the page without verified exports or an archival plan, it didn’t just remove a forum; it jeopardized the public’s record.

Put together, the picture is this: Lindke and Garnier anchor the idea that an official, government-branded page used for district business is a state-action space constrained by the First Amendment; the Brown Act polices how any board-level decision to erase that space must be made (in public, not by serial text); and San Jose plus California retention law require that the conversation conducted there be preserved for the public’s memory. Deleting the page at the height of criticism doesn’t neatly dodge those frameworks—it collides with all three.

Bottom line

Erasing a forum is not the same as enforcing rules within it. Dehesa chose erasure. Whether that passes a narrow legal test or not, it fails the community‑trust test. Parents deserved guardrails; they got a padlock.